The Slocum mission and GROOM RI

- April 1989: the beginning of a dream

In April of 1989, the magazine Oceanography published the vision of the famous oceanographer, Henry Stommel. He dreamt of a world where autonomous, buoyancy driven, underwater vehicles surveyed the world’s oceans. The peer-reviewed article titled “The Slocum Mission” chronicles a stunning near future where Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) harvest subsurface data on an unprecedented scale and frequency.

- The Slocum

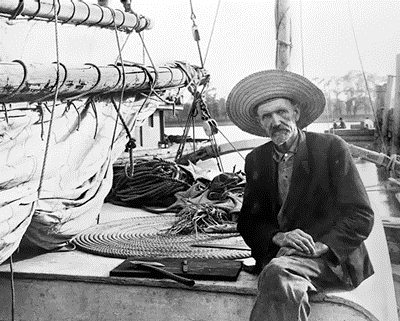

The Slocum float is named after Joshua Slocum, the first person to sail single-handedly around the world, averaging 1 knot speed . Like Slocum the sailor, Slocum the AUV can travel long distances at almost the same speed, but unlike the sailor, this AUV explores the deep seas while gliding thousands of kilometers through various bodies of water.

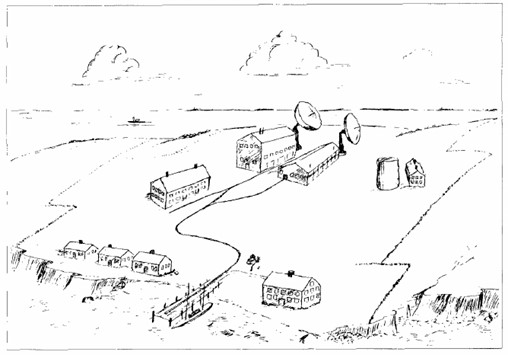

The Slocum Mission Control Center on Nonamesset Island. Stommel’s comment :“Each Slocum reports into Mission Control via satellite about six times a day.”

- Stommel: an inspiration for young oceanographers

Stommel the oceanographer, was inspired by Slocum the adventurer. In turn, Stommel inspired younger oceanographers and pioneering ocean engineers to design, build, and operate long distance, high endurance gliding AUVs which were soon commonly called (underwater) gliders. Three decades after he published his foresight of fleets of sentinel Slocums circumnavigating the globe, Stommel continues to inspire researchers to dream, innovate, and develop new methods to sustainably monitor the world’s ocean bodies and seas. These innovative methods to explore the ocean bodies with marine robots, AUVs and also autonomous surface vehicles, increasingly contribute to widespread ocean observations for science, industry, and regulatory agencies around the world.

The EGO community

The EGO (Everyone’s Gliding Observatories) network was launched by several teams of oceanographers, interested in developing the use of gliders for ocean observations and willing to set up a strong glider community. EGO was first composed of scientific teams from France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom and EGO stood for “European Gliding Observatories” for a while but it is now more appropriate to call it “Everyone’s Gliding Observatories”, as colleagues from Australia, Canada, South Africa and USA, from academia or industry, have joined this open community.

The EGO acronym was chosen because gliders are among the first intelligent marine robots. Dedicated to oceanography, they do react to their environment. In line with Asimov stories, the EGO acronym suggests that gliders will probably develop some kind of personalities as their intelligence will increase.

This idea of this glider group emerged in October 2005 and since then, collaborations have been developing. Experiments with international fleets of gliders have been carried out and EGO Workshops (including “Glider Schools”) are organized every year or so to present and discuss both scientific and technological issues.

We intend to facilitate glider experiments through networking and support within the EGO community. We collect information about the worldwide glider activity, references, tutorials, technical notes and links, and we support the development of software related to gliders. Our goal is to share the efforts needed by glider data collection as a community, and support the dissemination of glider data in global databases (like Coriolis Data Center) in real-time and delayed mode for a wider community.

In 2010, a core group from the European EGO groups launched two projects, GROOM FP7 and EGO COST Action (see section Projects), to progress toward the creation of an actual European Research Infrastructure for underwater gliders. And some years later, the GROOM II project consolidates these first initiatives that now also include other types of marine autonomous vehicles.

GROOM RI, a Cutting-Edge Marine Research Infrastructure

Inspired by Stommel’s vision, a group of European scientists and engineers have started a new European marine research infrastructure (MRI) to coordinate and integrate their activity with the variety of long range observing Marine Autonomous Systems (MAS) available today , and extend Stommel’s pioneering vision with current and future technologies. The Gliders for Research, Ocean Observation & Management: Infrastructure and Innovation (GROOM II) Project is the European project developing this marine robot infrastructure. GROOM II aims to design and establish a cutting-edge MRI, GROOM RI, that provides access and expertise in marine robotics – with an emphasis on gliders and long-endurance surface and autonomous vehicles.

- A distributed infrastructure over Europe

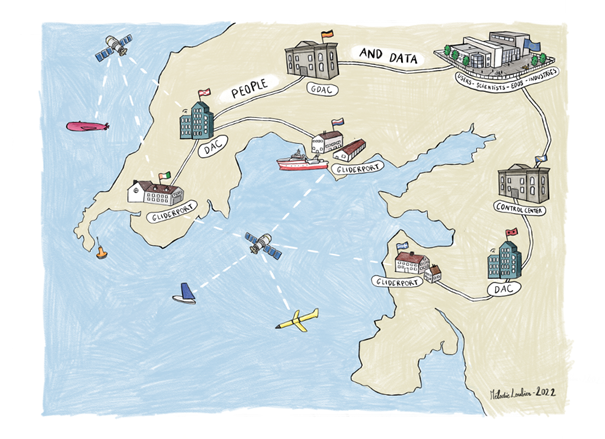

The GROOM RI concept : a distributed ensemble of “gliderports”, data and control centers, calibration and hardware facilities, and a central hub providing access to the users.

As most existing MRIs, GROOM RI coordinates several European capacities for observation at sea. This infrastructure promotes a collaborative approach to collect and share oceanographic data, which includes the complex activity of maintaining at sea over long periods a large number of gliders, as well as long range surface or underwater autonomous vehicles. Other important capacities of the GROOM RI distributed infrastructure include supporting marine robotics testing, development, and training. As a pan-European distributed RI facilitating marine research and observations, GROOM RI is similar to DANUBIUS-RI which develops interdisciplinary research on River-Sea Systems, or Euro-Argo which objective is to organize the contributions of the member states in the global Argo programme.

GROOM RI brings together marine robot operators, scientists, sensor and platform manufacturers, and data managers to share their results, experience and ocean knowledge. Since the publication of “The Slocum Mission”, ocean researchers have collaborated on various projects over the decades to flesh out the distributed GROOM RI concept.

By being the centre of expertise in marine robotics, this permanent infrastructure aims to become the central hub connecting today’s more distributed glider ports currently operating 150 gliders. These MAS ports – we called them also “gliderports” – around Europe provide various services from mission planning, glider piloting, vehicle maintenance and operations to training, data management, sensor calibration and integration.